Proper techniques for safe and efficient use

by Chris Pye

This article was first published in issue 39 of Woodcarving Illustrated.

There is your piece of wood: a willing or unwilling victim of your designs, and then there’s you: intent and ready to carve. What’s in between? Your carving tools.

We’ve looked at how important it is to have a sharp and properly configured cutting edge, set at the correct cutting angle. Woodcarving is all about making the tools work for you.

I’m going to describe two grips that I use when I’m carving without a mallet. These two grips are safe and give you excellent control of the tool while carving.

Basic Grips

I use one of these two grips according to what I’m doing in a particular carving situation. I swap between these two hand positions continuously and without thinking.

Even though the grips are substantially different, there are fundamentals, or “golden rules” that pertain to both:

- Both hands are on the tool: one will grip the handle (the “handle hand”); the other will be gripping the blade in some fashion (the “blade hand”).

- Both hands work together: if you find yourself using and focusing on one hand, you are only partly in control.

- Part of the blade hand rests on your wood (or perhaps the bench): this greatly increases your ability to control the tool.

While I’ll cover the basic techniques, all of our hands and muscle controls are individual. You will need to play around with what you’ve got, and of course, practice until handling the tools this way becomes second nature. Use a clean, flat board of wood that is easily carved for practicing. To begin with, work across the grain; you’ll find the wood shavings simply fall off.

Low Angle Grip

With the low angle grip, both hands work together to control the forward movement of the running cut and its shape. Mastering this grip allows you to make consistent lines and grooves. The ability to control your tool and repeatedly produce consistent results will greatly enhance your carvings.

Because you will carve from left to right and right to left, it is extremely helpful to develop a degree of ambidexterity and be able to swap the tool between hands. Since the grip probably feels awkward to begin with, begin practicing in both directions from the start. Keep your elbows in and

use your body.

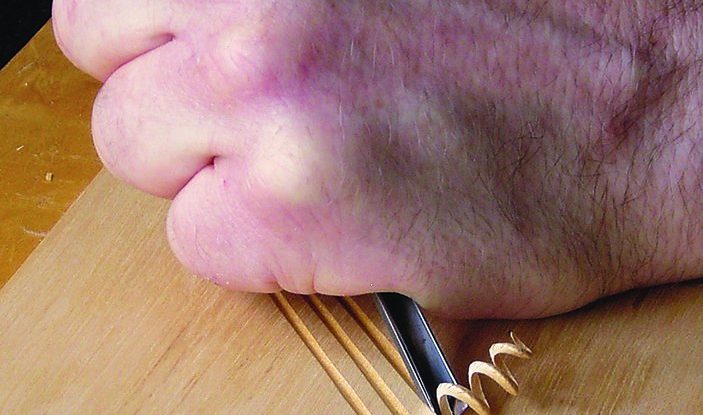

Low Angle Grip: Extending the thumb of your blade onto the handle increases control. Anchor your hands to the workpiece with the heel of your blade hand.

The Grip:

1. With one hand, take a firm hold of the tool where the blade joins the handle; in most carving tools this will be across the ferrule and shoulder. The little finger end of your hand will be towards the cutting edge and thus grip some of the blade, while the thumb end of your hand closes around a portion of the handle.

2. Increase the control this hand has over the tool by extending your thumb along the handle.

3. The heel of your blade hand now rests on the wood. Sometimes I will rest the whole of my forearm on the wood as well.

4. With the other hand, grip the handle in whatever way feels comfortable. This hand will do the pushing.

5. Here’s the secret of control: while pushing the tool with one hand, you must resist the forward movement with the other.

Thus there is a tension between your hands while you are moving the tool forward; a balance between the two forces: pushing and resisting. The difference allows the tool to advance and cut in a controlled manner, starting and stopping at will.

Practice:

1. Take up the grip with a V-tool (or narrow deep gouge).

2. Run a simple, shallow, straight groove away from you. When you get to the far end, lower the handle and exit the groove. Control the start and stop point while maintaining a constant depth.

3. Run another groove a little to one side, trying to copy the first exactly. Being able to copy the line is a demonstration of tool control, which is your aim of course.

4. Repeat this a few times. Remember to push and resist at the same time—but relax your shoulders and only use the minimum effort you need to make the cut.

5. Now reverse hands! If your right hand was gripping the handle first, you will now grip it with your left. You may find it feels awkward at first, but do persevere for there are real advantages to being able to carve easily and efficiently in the opposite direction. Repeat the running cuts exercise. These “running cuts” are the sort of thing you’ll use for veins or lines; you always want these to be smooth and flowing.

6. With your right hand on the blade, run a line from left to right. Copy a few times.

7. Without changing hands, run a line from right to left. You’ll see this is very awkward without yoga-like contortions, turning the wood around, or moving

your body.

8. Now swap hands (so the left hand is on the blade), and run that line from right to left again.

I hope you can clearly see the advantages of being able to swap hands when you are using your carving tool at a low angle like this, even if the grip still feels strange at this point. It is the same advantage no matter what tool you are using.

Delta Grooves

9. Now create short delta-like grooves—V-cuts starting shallow and deepening towards the end of a line. Use a 60° V-tool and start your V-cut lightly, but then raise the handle to send the cutting edge deeper into the wood. To stop tidily, you must practice resisting with the blade hand.

10. Line up a series of identical delta cuts, and use the corner of a skew chisel or knife to nip off the ends. Angle the cut out at 60°, the same as the angles of the walls cut by your V-tool. This allows light to reflect nicely off the end wall and is one of those extra little details that makes for excellent, rather than just good carving. This exercise is very good practice in starting and stopping, and again is demonstrating that all-important control.

Curving Lines

11. Now, with the blade in your right hand, run a curving line clockwise across the block. You’ll see that you can do this readily, because you can pivot on the little bone in the heel of your blade hand. Copy the line a few times.

12. Without changing the grip, try to run a curving cut counter-clockwise. You’ll find it less smooth, because you are going against the natural pivoting action of the blade hand. You will need to swap hands to make similarly easy cuts in the opposite direction.

13. Swap hands, and try that counter-clockwise cut again. Now you’ll find you can use the smooth natural pivot of the blade hand to your advantage. Again, the case for ambidexterity when carving at low angles. Essentially you are making the best, most efficient use of the natural way your hands work. Being able to swap hands like this will make carving so much easier and significantly increase the quality of your results. You don’t have to be truly ambidextrous—I’ll always be right dominant—but you should work towards feeling competent carving in your weaker direction.

14. Experiment with these curving lines and swapping hands. To produce a deeper cut, you need to lift the elbow of the handle hand quite high. You’ll find the low level grip now feels awkward, loses power, and puts a lot of unnecessary strain on the elbow joint. To produce deeper cuts, you’ll want to transition to the “high angle” grip which I sometimes refer to as “pen & dagger.” Knowing when to use which grip comes with practice and developing a degree of confidence using both types of grips.

High Angle Grip

The high angle grip is used when the tool is presented vertically to the wood or when you want to create depth with your cut.

This high angle grip can feel a little alien to begin with; although I’ll describe it as best as I can, you will need to play around and sort your fingers out—you’ll be glad to hear that there is no need to swap hands with this grip!

High Angle Grip: Use your non-dominant hand to grip the handle. Anchor your hands to the workpiece with the middle finger of your blade hand.

The grip:

1. Start by placing a gouge (say a #6 x 1/2″) perpendicular to the wood and holding the handle somewhat like a dagger in your non-dominant hand.

2. Place the tip of the middle finger of your dominant hand onto the wood and tucked tight up behind the bevel of the tool, thus bridging tool and wood. Bring up the ring and little finger behind the middle finger to support it, and bring the heel of your hand down onto the wood surface.

3. You should have a finger and thumb of your dominant hand remaining. Use these to grip the blade. By resting between the wood and bevel, the middle fingertip acts in the same way as the heel of your hand did in the low angle grip, maximizing control. This basic hold adapts as we start using the tool.

Practice:

1. Push down with the handle hand, putting your shoulder behind it for weight, and force the cutting edge into the wood. The impression you leave will be the “sweep” of the gouge and the cut is a “stab” cut.

2. Ease back on one (leading) corner of the blade, advance the cutting edge a little along the cut, and stab it in vertically again. You must lift the leading corner of the cutting edge clear of the groove in order to not plow up the wood.

3. If you keep doing this, you will shift the cutting edge of the blade around in a complete circle, and you will need to adjust your fingers to cope! At one point you will need to flip the blade hand smoothly around so that instead of the blade being supported by the tip of the middle finger, it now nestles on the back of the finger in the groove between the nail and first joint. Both hands work together with the handle, helping to rotate the tool. Keep gripping and controlling the blade by pinching it between finger and thumb. If you were to do this same exercise with a small, deep gouge (#9 x 1/8″), the wedge effect of the bevel would pop off the little bit of wood in the middle. This is a traditional carving technique, and the resulting hole is called an “eye.” You would most likely use this technique in carved mouldings and acanthus leaves for example.

4. Stab around the circle clockwise and counter-clockwise until you feel the finger movement starting to sort out and controlling the tool becomes easier. Besides cutting vertically, you can use this grip at any angle greater than 60°.

5. Run the tool around in the same fashion, but with the handle angled out, so the gouge depicts a cone as it passes through the air, with the point centered on your work. Use your thumb to push the blade forward in sync with the hand rotating the handle. Notice how the hands seem to be crossed when the gouge comes in from one side and apart when approaching from the other side. Also see how the handle hand changes from a “dagger-like” grip to one in which it pinches. This is an extremely important grip to master, combining control with finesse and, when you can involve your shoulder, a fair degree of power. I use it for setting in or for detail work—any time the tool is presented vertically to the wood.

To get the most from this way of carving takes time as you will need to develop the gripping muscle between your index finger and thumb. You can always tell the hands of a traditional carver, because they have a well-developed gripping muscle in this area (red arrow).

6. Try using this grip to take out small crescents and lozenges, approaching from either side at an angle. Use the high angle grip and a single cut from either side. You must use the corners of your gouge in a scooping action to clean up the bottom of the trench. A fishtail gouge with pronounced corners is ideal here, but a regular gouge will do.

Putting the Grips Together

A good way to consolidate and practice both these grips is to try some light, surface, ornamental carving, and use what you have done already to create leaves, flowers, or wheat. Start by “drawing in” the main stems with your V-tool; then add deepening V-trenches, “eyes”, crescents, and lozenges to assemble the other details. Work hard to get your lines flowing and smooth and all of the details cut cleanly—these are the fundamental elements that make a carving look good.

If it doesn’t work out, plane the surface off, and have another go! Remember, it’s only a piece of wood, and you’ll need to get through lots to gain confidence and competence.

Above all, have fun. Play and experiment!

A practice board of simple surface carvings will allow you to develop the techniques we learned in the exercises.

About the Author

Chris Pye is a master woodcarver, instructor and author. He has written several books and offers one-on-one instruction at his home studio in Hereford, England. You can visit Chris’s teaching website at woodcarvingworkshops.tv. He also maintains a monthly e-mail newsletter and website on woodcarving at www.chrispye-woodcarving.com. For more on the basics of woodcarving, check out Chris’ series of books Woodcarving Tools, Materials, and Equipment.

Discuss this material on the Woodcarving Illustrated forums.