Create a worn, antiqued look for your carvings by finishing with flames

By Curtis Badger

Photography by Tom Badger

This article originally appeared in Woodcarving Illustrated Spring 2006 (Issue 34).

Bob Swain spends days carving an intricate dragon from 10 separate pieces of white cedar. Finally, with the pieces assembled, the form takes shape. The head is high and alert, the body curves in a graceful arc, the wings and crest sweep back as though the dragon is moving at great speed. Bob turns the piece from side to side, and reaches for a well-worn paintbrush. He soaks the brush in dirty mineral spirits, douses the carving, lights a wooden kitchen match, and in seconds the dragon is ablaze.

Bob Swain spends days carving an intricate dragon from 10 separate pieces of white cedar. Finally, with the pieces assembled, the form takes shape. The head is high and alert, the body curves in a graceful arc, the wings and crest sweep back as though the dragon is moving at great speed. Bob turns the piece from side to side, and reaches for a well-worn paintbrush. He soaks the brush in dirty mineral spirits, douses the carving, lights a wooden kitchen match, and in seconds the dragon is ablaze.

Bob uses fire as a complement to carving and painting his wood sculptures. The dragon emerges from the flames with no structural damage, but with a dark, rich patina that later shows through a thin application of oil paint. “Burning makes a carving appear worn and aged, like it has been handled and used a lot,” Bob said. “And that’s a quality I like. I want them to be handled. I want people to feel the form and texture. It involves a sense other than vision.”

It is something of a miracle that Bob sculpts wood at all. In 1965 he was a college student majoring in business. He and some friends were heading off on a weekend trip one rainy Friday night, when the car went out of control and struck a culvert, and Bob’s spine was snapped. Barely out of his teens, Bob faced months of rehabilitation and a future in a wheelchair. However, the accident seemed to kindle some latent spark of independence in Bob. Rather than giving in to the physical limitation, he uses it as motivation. He completed rehab, moved back home, and began running the family’s farm supply business, expanding it to include greenhouses, ornamental plants, and garden tools.

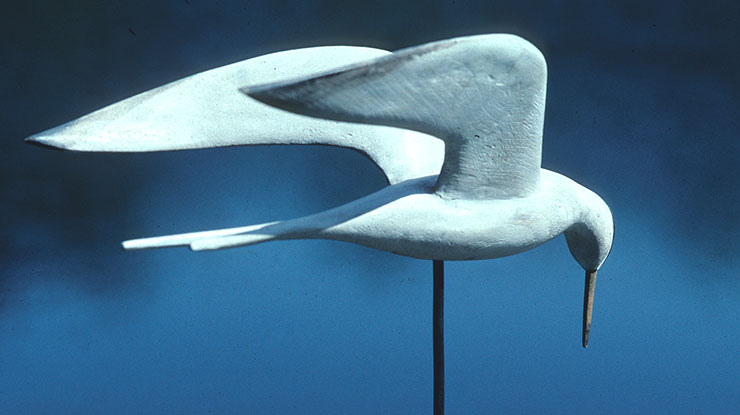

Bob lives on Hunting Creek on Virginia’s Eastern Shore near the Chesapeake Bay. He began carving 20 years ago when he began collecting antique hunting decoys. Bob enjoys the weathered patina of old decoys, and attempts to replicate it in modern carvings. Bob admits that early in his career he used the wheelchair to get noticed and to stand out from the legion of bird carvers who attended the art shows and carving competitions. “It helped people remember me,” he said.

Now the 60-year-old carver spends 10 to 12 hours a day carving, despite being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease nine years ago. The additional physical setback seems to have made him even more driven to carve. “With the Parkinson’s, it’s like blinders on a horse—I can’t deviate from the straight and narrow,” he said. “I don’t know how much longer I’m going to be able to do this, so I’m very focused on it now.”

Bob studied with the noted decoy-maker Mark McNair, who uses fire as part of an aging process, and Bob adapts the process for his own work. “Mark uses fire on a very limited basis in his work, but I use it extensively,” Bob said. “I burn the raw carving with stained mineral spirits to provide a base color of aged wood. And then I burn the oil paint as I apply it to darken and enrich the color. Finally, I scrub the carving with soap and water, and that removes any burn residue and thins the paint enough to let some of the aged wood show through.”

While Bob’s early interest in woodcarving reflects his passion for antique hunting decoys, his work has evolved to cover a wide range of subjects, from the dramatic to the whimsical. In his studio overlooking Hunting Creek you will see a carving of a peregrine falcon with a dying shorebird in its talons. You also will find a carving of a cow jumping over the moon, a carved cat with moving joints sitting on the edge of a shelf, and several carvings of dragons.

Using Fire to Finish a Carving

Bob’s general procedure is to apply paint to an area, burn the paint, and buff it with a bristle brush. He uses Ronan brand oil paints, which are very concentrated, dense paints used in the sign-painting business. Bob applies the paints with worn brushes, blending the colors on the carving.

Bob is also very careful to only light the carvings on fire over a concrete floor with no combustibles near it. Use common sense if you use any of his techniques—fire can be very dangerous.

TIP: A Thin Coat of Paint Looks Best

TIP: A Thin Coat of Paint Looks Best

Bob uses thin washes of paint. If he gets too much on the carving, he will wipe it off with a cloth dampened with paint thinner. Here you can see that the paint on the wing got too thick. After wiping it with mineral spirits, the paint on the wing is now lighter, with some of the patina and texture of the wood showing through.

Curtis Badger, a former director of publications for the Ward Museum in Salisbury, Md., has written widely about natural history and wildlife art. He has done numerous books on bird carving for Stackpole Books, and he recently wrote a book on the natural history of the Atlantic Coast entitled The Wild Coast, published by University of Virginia Press. Tom Badger is Curtis’ son.