Despite hundreds of profiles, sizes, and shapes to choose from, they all remove wood

By Roger Schroeder

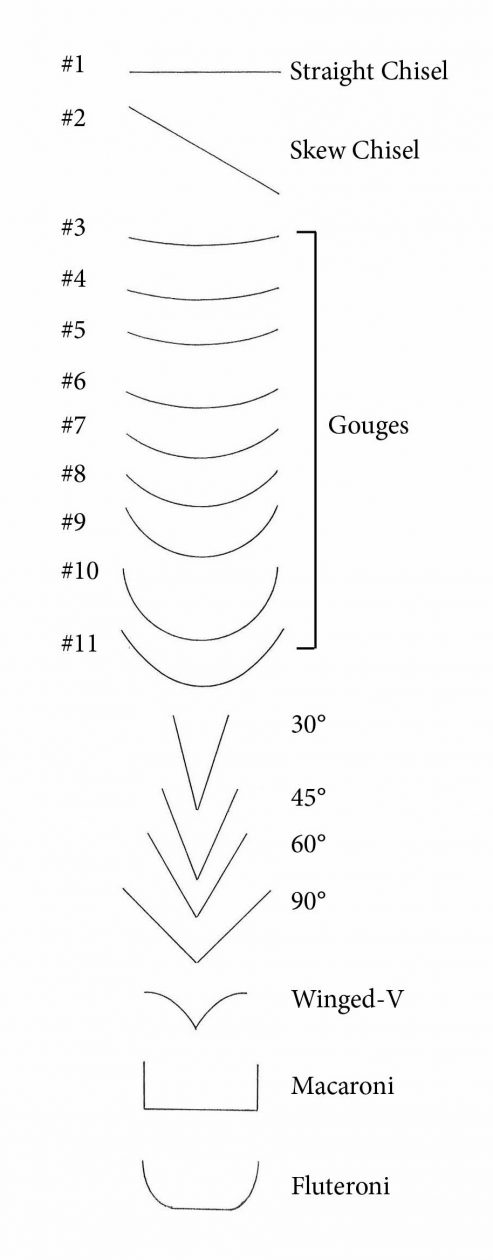

To a carver, chisels, gouges, and V-tools are all chisels. While that simplifies the description, it is not accurate. The cutting edge of a chisel is a rectangular shape, while the cutting edge of a gouge is curved. A V-tool consists of two rectangular profiles brought together at a common point.

|

ChiselsThis illustration shows a straight-edge chisel beveled on one or both sides. Bevels are designed to draw the tool in or out of a piece of wood. A double-beveled chisel can be used with either side up or down and the edge will not pull in or out. A single bevel draws the edge into a work piece if the bevel is up and pulls the edge out of the wood if the bevel is down. Single-beveled chisels are generally used in carpentry and general woodworking. When the bevel is down it creates very flat surfaces. Carvers usually prefer double-beveled chisels because they do not dig into or out of the wood. However, some carvers prefer single-beveled chisels because they like using a tool that can be pulled in or out of the wood. If they don’t want that option, they simply use the chisel bevel side down to lever the cutting edge out of the wood. |

The Numbers GameMost carving tool manufacturers use #2 to describe a skew chisel. Beveled on one or both sides like a #1, the cutting edge is skewed or angled at 60°. When it is used with a slicing motion—think of a guillotine—it easily pares wood away and fits into tight corners that a #1 can’t reach. If the bevel is on only one side, you will need a pair that comes right-handed and left-handed. As the numbers increase, the tools lose their rectangular cross section and become gouges. Next in line for most carving tool manufacturers is the #3 gouge, although pfeil® Swiss Made Tools offer a #2 sweep and Ashley Isles produces a #2 1/2 finishing gouge. Often described as a grounding tool, the #3 works best to level or flatten concave areas. When working on rounded surfaces, the corners of the tool won’t dig in unless you try to make very aggressive cuts. Whether carving in high relief or sculpting something in the round, the #3 is one of the most useful gouges, and you will find it in every professional carver’s collection of tools. As the numbers increase beyond 3, the sweeps get progressively more curved—up to a point. The profile becomes U-shaped at #11. The #11 is often called a veiner because this shape was among the mainstay gouges of carvers doing veins in foliage. Today, even caricature carvers enjoy the #11 because it outlines easily without leaving a sharp line in the wood. |

|

Get Out the Dictionary

After #11, the tool designations get quirky. The numbers describe the shape of the blade, not the curve of the cutting edge. Based on the Sheffield Illustrated List, a 19th-century catalog that helped set tool shape standards, curved or bent blades are numbered 12 to 20. Spoon-shaped chisels and gouges are in the 20s and 30s; gouges that have a back-bent shape range from 33 to 38; tools such as macaroni and fluteroni lurk in the upper 40s and low 50s; and special spoon bits are in the 60s. To add to the confusion, expect to find tools described as dogleg, fishtail, allongee, and in-cannel.

|

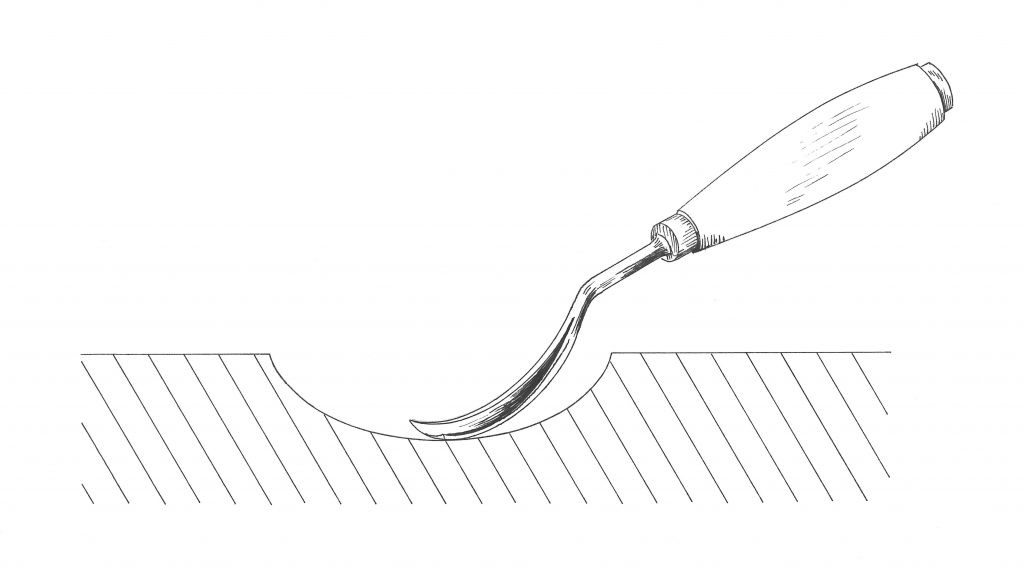

To help clear away the fog that probably settled with the introduction of some of these new names, let me start with bent tools. These are exactly like their straight counterparts except that they are curved along the length of a blade. These curves change the angle at which the edge begins to cut, making it easier to cut into recesses such as bowls and deep relief work. The gouges, which come in long- and short-bent styles, also work well to undercut an area. |

| The spoon gouge is used to make concave cuts in tight areas. The end of the tool resembles a common spoon because of the short curve at the end of the blade. The shape of this tool raises the handle angle significantly—to almost 90°. This position allows you to make a nearly right-angle cut. |  |

|

The back-bent gouge cuts convex profiles in places where top clearance restricts the use of straight gouges. To cut these profiles the curve is reversed so the cutting edge is convex instead of concave. This gouge is actually used in an upside-down position. It is a specialized tool, but very useful when doing ornamental work with lots of curves and recesses. |

| The macaroni tool, which looks like a squared-off veiner, has three working edges with sides at right angles to the bottom edge. Ground with an outside bevel, the tool functions as both a chisel and a V-tool, and is designed for working backgrounds in relief carving.

The fluteroni also has three beveled edges, but each side has a small radius on both sides of the cutting edge. It fills the gap between the macaroni tool and a gouge. Most carvers familiar with the macaroni and fluteroni tools do not use the entire edge in one cut—they tend to use one side or the other. |

|

|

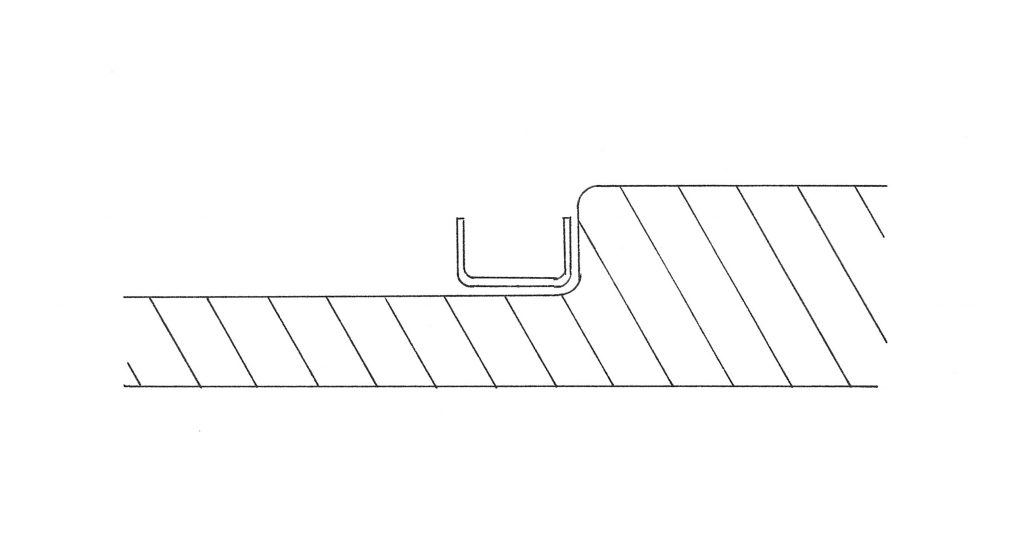

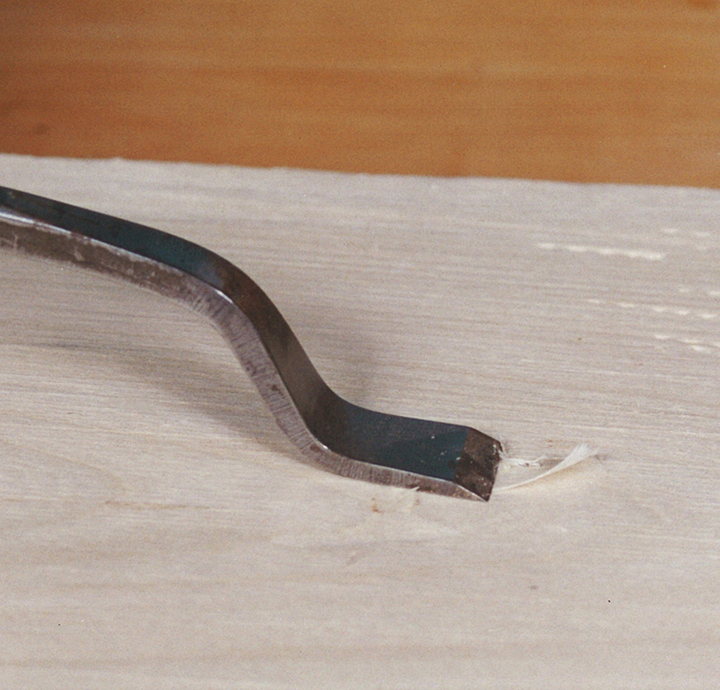

The blade of the dogleg chisel is bent, resulting in a shape that looks like a step. Like a carpenter’s chisel, it has a single bevel on the topside of the tool. Because of the location of the bevel, it is a good tool for finishing flat recesses or backgrounds on a relief carving where clearance is limited. |

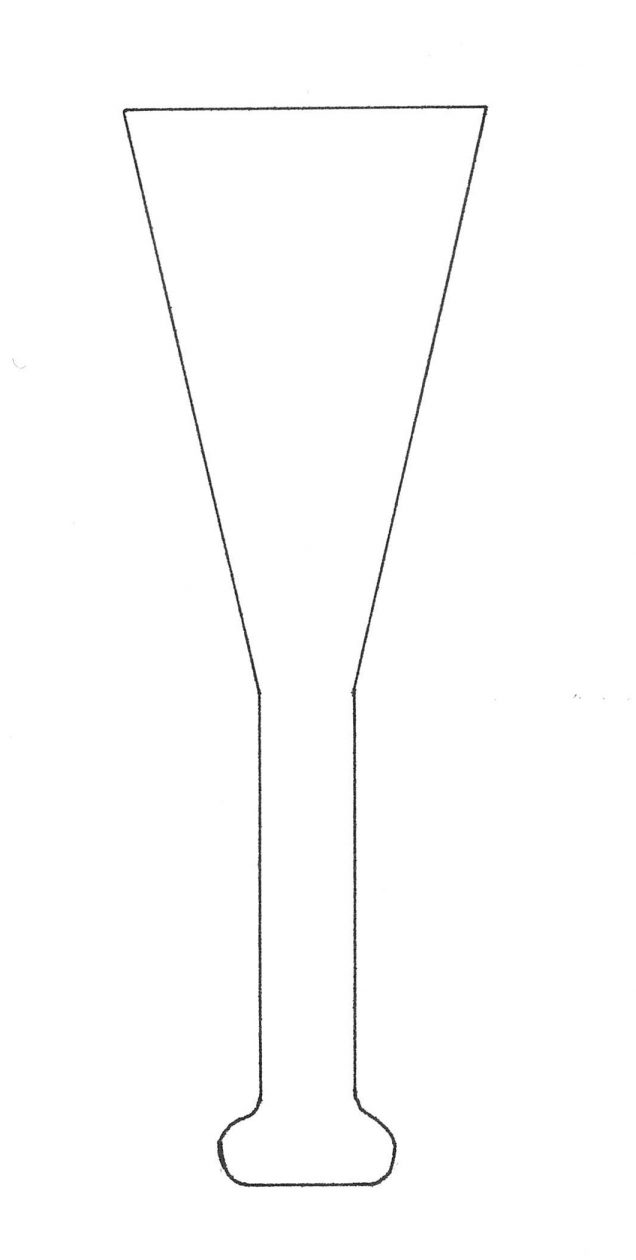

| As the name suggests, the fishtail gouge has a partially tapered profile. Useful for delicate wood removal, it is also good for undercutting and cleaning out corners. The sweeps typically range from #1 to #9. Some palm-size tools come as bent fishtails. |  |

|

Allongee is a French word for elongated. Similar to the fishtail gouge, the allongee has a shank that tapers back continuously to the handle. It is designed for roughing out and heavy wood removal.

Most of the gouges you will come across have the bevel on the outside of the curve. But some do have a bevel on the inside. Called in-cannel, this style of gouge works best as a paring tool for convex surfaces. One carver I know, who excels at abstract sculpture with many convoluted surfaces and voids, finds in-cannel gouges essential. In fact, he fits his blades with extra-long handles so that they can reach deep into the recesses of his pieces. |

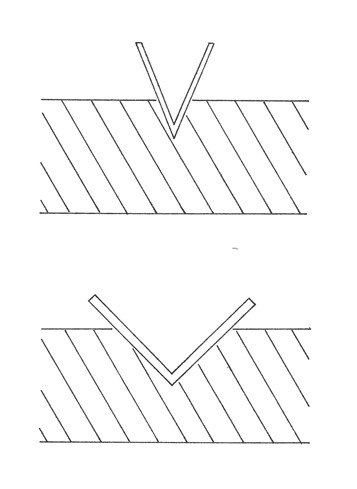

The V-ToolIn the Sheffield number system, V-tools range from #39 into the 40s. Some carvers say that the V-tool is just two chisels joined to form a V. That makes sense because the tool can perform as a chisel if held so only one cutting edge is doing the work. But the primary function of this tool is to separate areas when outlining, adding detail, texturing, or undercutting. It is also called a parting tool. The difference between the V and the gouge, even a #11, is that the V gives you a wall rather than a valley. Since nearly all V-tools have two straight edges, measurements are based on the angles of the V. Angles are usually 30, 45, 60 and 90 degrees. Occasionally a toolmaker produces a smaller angle such as 24°, which results in a very fine line. |

|

|

Typically, the tighter or narrower the V angle, the harder the tool works through the wood. This is because the tool’s cutting edge has an inside dimension that is smaller than the outside dimension. In effect, the cutting edges make a channel smaller than the width of the tool. This is not particularly noticeable with a 90-degree V-tool because the cutting edges can easily ride up in the channel to accommodate the change. You feel more resistance with a 30-degree V-tool because the sides are more perpendicular and can’t ride up as easily through the wood. Narrow V-tools are best for making cuts that are both shallow and narrow or for cleaning out corners where the cutting edges are free to move.

An exception to the straight-edge V is the winged V-tool, meaning that both side profiles have curvature. The winged V softens work by rounding the top of the carved edge. Expect to find this specialized tool in the kit of an ornamental carver. |

Handles, Tangs, and BolstersAt one time handles were sold separately. Today you will find every chisel, gouge, or V-tool fitted with an ash, beech, hornbeam, or perhaps a rosewood handle. The handle shapes are usually round or octagonal with straight sides or a slight bulge, although Flexcut™ Tools offer a more ergonomic design. Octagonal or asymmetrical handles are easier to grip securely and give a reference point as to where the tool is in your hand. You can also feel the handle rotate if your grip begins to slip. And there’s the added benefit of the tool not easily rolling off the workbench. |

|

|

|

Most palm tools have short stubby handles that are meant to be palmed instead of struck. The design does not remove a lot of wood quickly, but you will find that they handle a lot of details, especially on smaller projects.

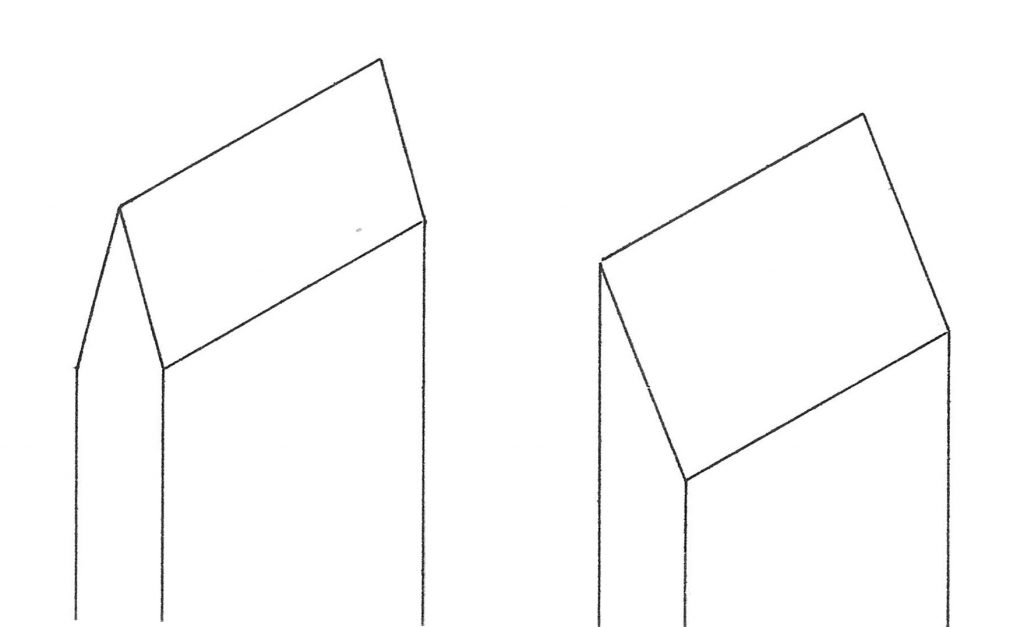

Handles are secured with either tangs or sockets. A tang is a spike that fits into a handle. Most top-quality carving tools have a bolster or shoulder that acts as a stop for the tang. But as much as 2000 years ago, sockets prevailed and did so for many centuries. A socket is a conical-shaped opening that accepts the tapered end of the handle. Because of the way the two components fit together, the handle is able to withstand heavy blows from a mallet. |

| Regrettably, the socket fell into disfavor, possibly because it is easier to forge a tang. Still, Japanese companies produce carving tools with sockets and a few other companies offer this style on heavy-duty carving tools. Expect to use them for large sculptures, not on small decorative projects.

Another feature to look for is a metal ring on the end of a handle. When struck repeatedly with a mallet, an unringed handle tends to mushroom. When mushrooming occurs, the blow from the mallet is dispersed and the handle tends to split and fall. The socketed tools I have come across, particularly the Japanese brands, usually have ringed handles. However, if not seated properly, a ring will chew up a wooden mallet or it will fall off with changes in humidity. Still, a combination of ring and socket makes for a superior tool, but a high price tag often accompanies it. |

|